3D TV

Back in the 1890s, when French cinema pioneers Auguste and Louis Lumière screened their early movie of a

train arriving at a station, legend has it that terrified members of the audience dived to one side to get out of its way. Despite all kinds of technological innovations in the decades since then, movies and

TV never again seemed quite so convincing. Just over a century later, it seemed affordable

three-dimensional television (3D TV) would usher in a new age of super-realistic entertainment, and the big TV manufacturers, such as Sony, Panasonic, LG, and Toshiba, soon started throwing their weight behind 3D technology. Unfortunately, consumers haven't been anything like as keen on watching 3D pictures at home and, for now at least, the revolution seems to have stalled: in 2013, The New York Times officially declared it "an expensive flop"; by 2017, leading makers such as Sony, LG, and Samsung had decided to drop the technology entirely. Despite that, 3D TV is still a fascinating technology, so let's take a closer look at how it works!

How and why do we see in three dimensions?

It's easy to forget you're an animal, pre-programmed to survive as long as you can by millions of years of evolution. Eat or be eaten is the basic law of a world most of us no longer live in (or want to)—but it's the world your body was built for. Some 25–50 percent of your (relatively) huge brain is devoted to processing information sucked in by your eyes and rebuilding it into a colorful three-dimensional "movie theater" that wraps around your head. But your visual system is much more than just a fancy interior designer: it's main purpose is to help you survive. Seeing things in three, rich and deep dimensions is a shortcut to understanding how the world is laid out: how close that 'gator is and whether you can escape it or, in modern terms, how far you need to stretch your hand to lift that cheeseburger to your lips!

Our brains generate a 3D picture largely by having two eyes spaced a short distance apart. Each eye captures a slightly different view of the world in front of it and, by fusing these two images together, our brains generate a single image that has real depth. This trick is called

stereopsis (or stereoscopic vision) and it's the seeing equivalent of using two

loudspeakers (or a pair of

headphones) to hear three-dimensional, stereo sound.

We take seeing in three dimensions for granted, largely because it's almost impossible to view the world any other way—even if you have just one eye.

Binocular vision (seeing with two eyes) is only part of how we perceive depth. With one eye closed, you'll find you can still get a pretty good idea of how the world is laid out thanks to many other "depth cues": lines recede into the distance in what we call

perspective; closer objects are generally bigger than distant ones and move more rapidly as you move your head (an effect called

motion parallax); nearer things have different surface

textures than further ones; and so on. That's why even flat, two-dimensional images (

photographs and moving images on movie screens and TV) give a

reasonable approximation to depth.

But if you really want to see a convincing image of the world, nothing beats putting a slightly different 2D picture in front of each of your eyes to jolt your brain into seeing them as a single, 3D image. And that's exactly the trick the latest 3D televisions are designed to play!

How does a 3D TV work?

There are several different ways of making a 3D TV, but all of them use the same basic principle: they have to produce two separate, moving images and send one of them to the viewer's left eye and the other to the right. To give the proper illusion of 3D, the left eye's image mustn't be seen by the right eye, while the right eye's image mustn't be seen by the left.

With glasses

The simplest way of achieving this is to display two different images on the TV screen (one for the left eye and one for the right) and make viewers wear special glasses so each eye sees only one of them.

The 3D technology most people have seen involves wearing eyeglasses with colored lenses, one red and one cyan, also known as

anaglyph glasses. Why these two colors in particular? The red lens is a

light filter that allows

only red light to pass through, while the cyan lens (cyan is an equal mixture of blue and green) allows through any color of light

except red. The point is simply that each eye isn't being allowed to see parts of the image that are being viewed by the other one, so each eye gets a slightly different picture of its own. While simple and inexpensive, this technique produces a relatively poor quality, monochrome picture and often makes viewers feel nauseous.

Photo: You'll need to wear anaglyph (colored) glasses to see images like this in three dimensions.

A much more promising system uses polarizing lenses in the glasses instead and two pictures that are projected from the screen using differently polarized light. Normally, light is made up of waves that vibrate in multiple directions at once as they shoot in straight lines through the air, while polarized (or "plane polarized") light is filtered so its waves vibrate in one direction only. If you fit glasses with two different polarizing filters, so the left lens receives only light vibrating up-and-down while the right lens receives light vibrating side-to-side, you can easily beam a different image from a TV set to each lens. The main drawback is that the TV set has to be fitted with polarizing filters as well, which bumps the cost up quite considerably.

A third option is more ingenious and involves people wearing

active-shutter glasses.

Battery powered, these have an

electronic shuttering system that opens and closes the left and right lenses, in alternation, at very high speed. At a certain moment, the left lens is "open" and viewing the left-eye image on the TV screen while the right lens is blocked. A fraction of a second later, the glasses reverse: the right lens opens, the left lens is blocked, and the TV picture changes so your right eye gets a slightly different image (or "frame") to your left eye before the whole process reverses again. And goes on reversing dozens of times each second. This technology is also called

alternate-frame sequencing.

Although the "shutters" work like little blinds that open and close in front of your eyes, they're actually

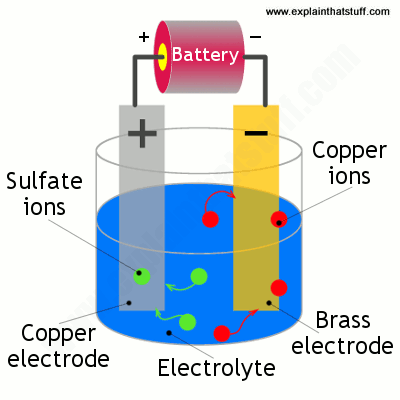

optical rather than mechanical: each lens of the glasses is fitted with a

liquid crystal display that instantly turns transparent (clear) or opaque (dark) when it receives an electronic signal. The glasses are linked by

infrared,

radio wave, or

Bluetooth to the TV set so they synchronize precisely with the rapidly changing pictures on the screen. Active shutter glasses like this are more expensive than passive ones (with colored or polarizing lenses), but give a better 3D image and can be worn for far longer without tiring people's eyes or making them feel sick. But the shutter system causes a significant loss of brightness and the flickering can be noticeable under certain conditions.

Without glasses

All three types of glasses can be a nuisance—especially if you wear glasses already—and that's why some people think TV manufacturers will need to be more ingenious and develop 3D technologies that don't need them. One option might be to use something like

holography, but that would probably mean redesigning TV cameras so they use complex

laser mechanisms that can capture depth, as well as patterns of light and color—and who knows how many decades that could take?

Another possibility is to use

lenticular TV screens, which work like those ridged

plastic,

lenticular printed book and magazine covers you see that show slightly different images as you tilt them back and forth. Lenticles are simply rows of very thin, parallel plastic

lenses that bend images either to the left or the right. Place them in front of a TV screen and you could, relatively easily, send two slightly different pictures to a person's left and right eyes so they see a single fused image in three dimensions. Although some TV manufacturers have successfully developed lenticular 3D TV, it does have a big drawback: you have to be sitting in exactly the right place, at exactly the right distance from the screen, so your two eyes receive their intended images in just the right way. Move too far to the side, the illusion will collapse, and you'll probably just see a messy blur. While it doesn't sound that practical for family viewing, lenticular 3D could work extremely well with laptop computers (generally viewed by one person at a very precise position and distance) and handheld

DVD players.

Why hasn't 3D TV caught on?

Why hasn't 3D TV caught on?

If manufacturers and program makers are going to have any incentive to make 3D TV sets and programs to show on them, consumers have to get behind the technology too—and, so far, that's not happening. Many people simply don't like the 3D experience or find they can't watch it for long. And there's just not enough compelling 3D content (TV programs and movies) to persuade people the investment is worth it. That leaves 3D TV technology in something of a Catch-22 limbo: it's not worth developing programs if people won't buy the sets; and it's not worth buying a set if there aren't any programs to watch on it. For now, at least, it seems unlikely that 3D TV will graduate beyond short-lived novelty—but it was an interesting experiment, while it lasted.TV makers would love us to think we can instantly get 3D versions of all our favorite movies and shows just by shelling out for a more sophisticated box of electronics—but, of course, it's not quite that simple. To start with, the world has about a century of 2D movies and TV programs; any new 3D equipment that's developed for the foreseeable future will need to be able to play all this stuff as well. More seriously, imagine the extra cost of producing 3D programs and (worse still) outside broadcasts. You want to watch superbowl in 3D? Fine! But that means you'll need at least two cameras (and maybe two trained operators) on the pitch for every one that's there today. So, potentially at least, 3D TV programs could be much more expensive to make.

A summary of how 3D TV works

Here's a quick summary of the four most common 3D TV technologies. In these diagrams, we're looking down on a person's head from above and comparing how two different images enter their two eyes in each case:

- Anaglyph: You have to wear eye glasses with colored lenses so your brain can fuse together the partly overlapping red and cyan pictures on the screen.

- Polarizing: You wear lenses that filter light waves in different ways so each eye sees a different picture.

- Active-shutter: The left and right lenses of your glasses are fitted with liquid crystals that effectively "open" and "close" at high speed, in rapid alternation, so your two eyes view separate images (frames) shown on the same screen.

- Lenticular: You don't need glasses with this system. Instead, a row of plastic lenses in front of the screen bends slightly different, side-by-side images so they travel to your left and right eyes. You must sit in the right place to see a 3D image.