Pasteurization

Go back in time a century and the idea of keeping fresh food for more than a day or so would have seemed not just ludicrous but positively dangerous: there's no surer way to make yourself ill than by eating food that's turning bad. Before electric refrigerators were developed in the early 20th century, people bought their food fresh each day and used it pretty much straight away. These days, with better technology for food preservation, some kinds of milk can be kept in a refrigerator for the best part of a month!

It's not just the cool box in your kitchen that makes this possible but the way the milk (and other foods) are specially treated before they reach your home. The key is a process called pasteurization, where fresh foods are heated briefly to high temperatures, to kill off bacteria, then cooled rapidly before being shipped out to grocery stores. By greatly increasing the shelf life of packaged foods, pasteurization has proved itself to be one of the most important food-preservation technologies ever developed. Let's take a closer look at how it works!

It's not just the cool box in your kitchen that makes this possible but the way the milk (and other foods) are specially treated before they reach your home. The key is a process called pasteurization, where fresh foods are heated briefly to high temperatures, to kill off bacteria, then cooled rapidly before being shipped out to grocery stores. By greatly increasing the shelf life of packaged foods, pasteurization has proved itself to be one of the most important food-preservation technologies ever developed. Let's take a closer look at how it works!How pasteurization was invented

Photo: Louis Pasteur. Engraving courtesy of US Library of Congress.

If you think pasteurization is an odd name to give to heating food, you're right; the process is named for its discoverer, French biologist Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), who stumbled on the idea in the mid-19th century while trying to discover exactly what made food go bad. Pasteur had trained in science and was working at the University of Lille, France when some winemakers invited him to solve a problem they were having: they couldn't figure out why certain of their wines were turning bad more quickly than others.

With the help of a microscope, Pasteur discovered that the yeast used in making wine and beer contains different bacteria. Some of the bacteria helps to produce the alcohol in the drink from sugar (by a process called fermentation), while other bacteria turns the drink bad after it's made. Pasteur's simple solution was to heat the wine briefly to kill off the harmful bacteria so the drink wouldn't go bad so quickly. This idea, which became known as pasteurization, proved hugely successful and was later adopted to help preserve a wide range of other food and drinks.

Building on his ideas, Pasteur turned his attention to medicine. With other scientists such as Robert Koch (1843–1910), he made a number of important contributions to the germ theory of disease: the idea that some diseases are passed between humans when bacteria carry them through the air.

How foods are pasteurized

Different foods are pasteurized in different ways. Even milk, virtually all of which is pasteurized, can be preserved by several different processes.

Traditionally, ordinary milk was pasteurized in large batches by heating it to around 60°C (140°F) for 30 minutes or so. It's also possible to use a faster process and a hotter temperature for less time: typically heating to 72°C (161°F) for just 30 seconds or so (or two separate periods of 15 seconds), which means the milk will then keep (in cool conditions) for a further 7–12 days (starting from when it leaves the processing plant, not when it arrives in your home).

The hotter the pasteurization temperature, the longer the milk will keep. In a slightly different process, milk can be pasteurized at a much higher temperature of about 140°C (290°F) for just 2–3 seconds, producing what's called UHT (ultra-high temperature) milk that keeps for months (that's the stuff you get in little plastic containers with foil lids in restaurants and hotel rooms).

The many other food products that can be pasteurized include almonds, beer, wine, canned foods, cheese, eggs, and fruit juice.

Who invented the pasteurizer?

Photo: Steam pasteurizer: A typical early pasteurizing machine, developed by Aage Jensen of Topeka, Kansas in 1903.

Although Louis Pasteur discovered the heat-treatment process that bears his name, the machines that carry out the process—pasteurizing large quantities of milk and other foods—were developed by other people. A quick search of the inventions on file at the US Patent and Trademark Office reveals dozens of different pasteurizing machines. The earliest seem to have been developed in the 1890s and include Gustav Schneider's Beer-brewing machine from 1892/1893 and Paul Puvrez's Apparatus for pasteurizing or sterilizing and cooling beersfrom around the same time. Numerous machines specifically designed for pasteurizing milk seem to have appeared between the 1890s and 1910s, including Enrique Taulis's Process of and apparatus for sterilizing milk(patented in Chile in 1894 and in the United States in 1896) and Jacob Woodyard's Device for heating, aerating, and cooling milk (from 1895). Some of the inventions incorporated pasteurization into ingenious food-processing contraptions, including Darius Payne's Combined pasteurizer, cream ripener, churn, and butter worker (from 1901). People are still developing new kinds of pasteurizers to this day: like heat-treated milk, ingenious ideas can last a very long time!

How a pasteurizer works

A typical pasteurizer is completely automatic. You pour milk in one end and it flows between a set of heating pipes or plates for a set period of time (long enough to kill off most of the harmful bacteria), then between a set of cooling pipes, before emerging from an outlet pipe into the bottles. Heating and cooling times and temperatures vary according to the type of pasteurization process being used.

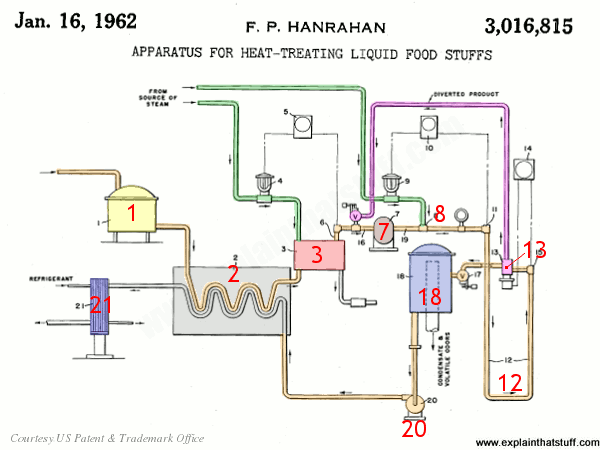

Obviously, that's extremely simplified! In practice, it's a bit more complex and convoluted. Here's an example of a pasteurizer developed by Francis P. Hanrahan for the US Department of Agriculture in the late 1950s, which uses steam injection to heat the milk. I've colored it to make it easier to follow, but it's not really necessary to go into all the details to understand it completely. Instead, I'm just going to give you a rough idea of the sequence with a few key parts highlighted in red. The milk follows the orange path from left to right and then back again. Steam is injected through the green lines.

Artwork: A typical steam injection pasteurizer that can be used with milk or other foods. From US Patent 3,016,815: Apparatus for heat-treating liquid food stuffs by Francis P. Hanrahan, patented January 16, 1962, courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office.

- Cool raw milk enters through the float tank (1, yellow) on the left at a temperature of about 4–5°C (40°F).

- It flows through a heat exchanger called a regenerator (2, gray), passing close to pasteurized milk that's flowing outward. The two milk pipes exchange their heat: the incoming milk is warmed up to about 38°C (100°F), the outgoing milk is cooled down.

- The now-warmed milk passes through a pre-heater (red, 3), fed by one of the steam pipes (green), and warms to 54°C (130°F).

- Now the milk enters the pasteurizing loop (marked out by 7, 8, 12, and 13). It's moved along by a pump (7), more steam is injected (8) to heat it to 72°C (161°F), and it flows around a long loop (12) for 15 seconds to keep it at that temperature long enough for pasteurization to occur.

- At point 13, a valve detects whether the milk is hot enough for pasteurization. If not, it's diverted up around the purple loop and back around the circuit until it is.

- Once the milk has been successfully pasteurized, it flows into a separator (18), still at 72°C, 161°F, where it's flash cooled to about 53°C (128°F) and deodorized.

- A pump (20) sends the partly cooled milk through the regenerator (2), so it cools further to 7°C (45°F) as it gives up its heat to incoming milk.

- A refrigeration unit (21) chills it to its final temperature for bottling and/or longer-term storage.

No comments:

Post a Comment