Vacuum cleaners

Even when your house is clean, it's absolutely filthy! That's because most of the dust and dirt in your house is way too small to see. Fortunately, most of us can live without knowing this kind of truth about our homes; a quick run around with the vacuum cleaner is enough to keep us happy. Twenty-first century homes are packed with dozens of appliances and gadgets, but vacuums are one of the few most of us simply couldn't live without. We all know vacuums suck up dirt—but how exactly do they work? And what makes a modern-style cyclonic cleaner different from an old-style bag cleaner? Let's take a closer look!

Even when your house is clean, it's absolutely filthy! That's because most of the dust and dirt in your house is way too small to see. Fortunately, most of us can live without knowing this kind of truth about our homes; a quick run around with the vacuum cleaner is enough to keep us happy. Twenty-first century homes are packed with dozens of appliances and gadgets, but vacuums are one of the few most of us simply couldn't live without. We all know vacuums suck up dirt—but how exactly do they work? And what makes a modern-style cyclonic cleaner different from an old-style bag cleaner? Let's take a closer look!Vacuum cleaner or suction cleaner?

The name "vacuum cleaner" is a bit of a giveaway when it comes to understanding how your machine works: vacuum cleaners work by suction. ("Suction cleaner" would be a better name than vacuum cleaner, in fact, because there's no actual vacuum involved. There is a difference in air pressure, but nowhere is there is an absolute vacuum.) If you've ever tried that cleaning trick with a tissue paper and a comb, you'll know how effective suction can be for removing dirt. If not, try it now! Wrap a piece of tissue paper around a comb. Breath out as far as you can and hold your breath. Place the comb and paper against your mouth. Now lean against a dusty armchair and press your mouth and the comb against it. Breath in sharply so, effectively, you are breathing straight through the comb. Take the comb away from your mouth and inspect the tissue paper. See how dirty it is!

Now imagine what would happen if you could keep this trick up for hour upon hour, just like a vacuum cleaner. Eventually, the dirt would build up on the tissue paper to such an extent that air would no longer flow through it properly. Your ability to clean—as a human vacuum cleaner—would be greatly impaired. This is a very important point: for a vacuum cleaner to work effectively, it has to maintain powerful airflow the whole time. If its bag is full or its filters are clogged up, its airflow will be dramatically reduced and it won't pick up dust. This is a problem that plagues almost every type of vacuum cleaner—even the bagless, cyclonic ones that are now so popular.

Cyclonic vacuum cleaners

Most vacuums used this "suck and bag the dirt" process until the late 1980s, when another British engineer named James Dyson felt it was time to go one better.

The trouble with old-style vacuum cleaners is that they suck in dirty air and blow it directly into the bag. The bag catches the dirt and the relatively clean (but often still quite dusty) air drifts back into the room. The longer you use a vacuum, the more the bag fills up. As the bag fills up, the amount of empty air it can hold decreases, so its ability to suck in more dirt is gradually diminished. The longer you go without emptying your vacuum, the worse the problem becomes. But emptying the bag is a real nuisance—and the dust can go everywhere!

Goodbye to the bag

Dyson decided to tackle this difficulty by doing away with the bag altogether. By this time, he was already a successful inventor manufacturing his own plastic garden equipment. His factory in England's West Country was plagued with dust, so he designed a "cyclonic" air filtering device to keep it clean. Using a powerful fan, it sucked in dusty air and spun it around at high speed like a centrifuge. Spinning the dusty air was an effective way to separate the dust out of the air. In a washing machine, the same principle is used to spin water from clothes at the end of the wash cycle. As the drum spins at high speed, the clothes fling against the edge of the drum and the water they contain is forced out through the drum's tiny holes. The same idea proved just as effective in Dyson's air filter. Spinning the dirty air separated out the heavy dust particles, which could be trapped and collected; the cleaned air could then be piped back into the room. Dyson's machine was so efficient and successful that he wondered why vacuum cleaners didn't use the same idea. He resolved to invent a cyclonic vacuum cleaner there and then.

Now it's very important to point out that Dyson did not invent the idea of using a cyclone to remove dust from air. In fact, if you look at his original patent (Vacuum cleaner appliances, dated 1983), you'll find he references quite a number of earlier inventions ("prior art"), the first of which is Bert M. Kent's Vacuum Creating and dust-separating machine developed 70 years before, in 1913, and patented in 1917. Kent clearly states that one of his objects "is to provide a machine... in which the 'cyclone' principle of dust separation is employed and the use of screens avoided."

Nor did Dyson invent the bagless vacuum cleaner. Back in the 1930s, Edward H. Yonkers, Jr. of Evanston, Illinois had noted how "the resistance to the passage of air through the bag is progressively increased during the normal accumulation of dust." To solve this, Yonkers proposed a suction cleaner with a sophisticated paper filter, in which "the whirling motion of the air around the conical filter serves to centrifugally separate the heavy particles of dust," which are then caught in a simple, bagless container. His invention became the very successful FilterQueen®, roughly four decades before Dyson!

So what did Dyson actually invent? His genius was to apply these two principles to a relatively compact, household vacuum cleaner and persuade people that it was more effective than the vacuum cleaners they'd become used to; it was as much about marketing as anything else—which is true of all great inventions.

Perfecting the invention

Between the late 1970s and the mid 1980s, Dyson built no fewer than 5,127 prototypes of his cyclonic cleaner. By the late 1980s, he was selling a bright pink cyclonic cleaner called the G-Force in Japan. It was large, clumsy, and expensive, but it earned him enough money to develop a more compact, affordable cyclonic vacuum called the DC01. During the mid-1990s, this new machine won countless design awards and soon became Britain's biggest selling vacuum cleaner—and machines based on this design are now sold worldwide.

Its secret is simple: because there is no bag to clog up with dust and dirt, the machine maintains a fairly constant airflow (informally, we say it sucks with exactly the same power). You still have to empty the dirt bin every so often, but the cyclonic action means a Dyson with a full dirt bin works equally as well as one that's just been emptied.

All this goes to show that, no matter how good an invention appears to be, someone can always make it better! (Talking of improvements, have you seen robotic vacuum cleaners that clean your home automatically?)

Key parts of a Dyson vacuum

So how does a Dyson actually work. First, let's quickly run through the key parts you'll find on one of the classic early models: the Dyson DC04 upright:

- Brush bar and air intake: The rotating brush under this bar loosens dirt in the rug so the vacuum's suction can pull it in. This is much the same as in a conventional vacuum.

- Height adjustment: Allows you to use the cleaner on hard floors, rugs, and other surfaces. When the vacuum is upright, the rotating brush is switched off. Air sucks in through an extension hose at the top of the machine instead.

- Powerful electric motor: This is effectively a giant fan that sucks in air and pulls it through the machine's cyclone and filters. As you've probably noticed, the motor in a vacuum cleaner gets quite hot after a few minutes; that's why the cool air it sucks in emerges from the machine somewhat hotter. On this Dyson, the air outlet is at the bottom, just underneath the dirt bin. Put your hand there and you'll feel warm air blowing out.

- Transparent plastic dust collection bin. The bin on this cleaner is absolutely full. One interesting thing worth noting on Dysons is the way their centrifugal, spinning action sorts dust particles into bands of different sizes, much like a centrifuge. You can just about see in this photo that there's a band of grit at the bottom of the bin, followed by a darker band of bigger dirt particles, with lighter fluff sitting on top.

- Cyclone: The cyclone is a large yellow plastic cone that points down into the dust bin:

The cyclone is the most important part of a Dyson. You can see from this photo that it's a tapering, cone-shaped piece of plastic with small holes in the top. The electric motor sucks dirty air into the top of the cyclone, where it whirls around at high speed. While the air is drawn through the cone, the dust spins around, drops down, and collects in the clear plastic bin beneath ready for disposal.Just above the cyclone is the upper dust filter (it's inside the gray cylinder, above the yellow cyclone, in the photo of the HEPA filters up above). There's one filter immediately above the dust collection bin and a second one at the bottom of the machine. The air passes through this second filter, for an extra clean, just before it returns to the room.

The cyclone is the most important part of a Dyson. You can see from this photo that it's a tapering, cone-shaped piece of plastic with small holes in the top. The electric motor sucks dirty air into the top of the cyclone, where it whirls around at high speed. While the air is drawn through the cone, the dust spins around, drops down, and collects in the clear plastic bin beneath ready for disposal.Just above the cyclone is the upper dust filter (it's inside the gray cylinder, above the yellow cyclone, in the photo of the HEPA filters up above). There's one filter immediately above the dust collection bin and a second one at the bottom of the machine. The air passes through this second filter, for an extra clean, just before it returns to the room. - Air hose: The electric motor sucks air through the Dyson along a network of tubes. The air is piped to the top of the machine, pulled and whirled through the cyclone, before returning through this pipe to the bottom of the machine. You can see the actual airflow through the machine in the photo down below.

How does a cyclonic vacuum cleaner work?

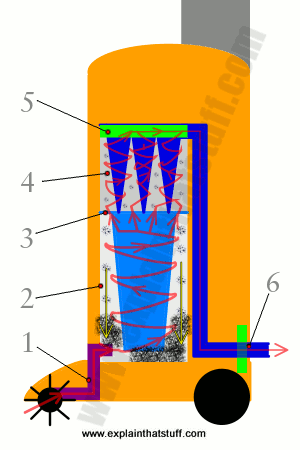

Now we've seen the parts, how do they all work? Here's a rough guide to what everything does as the air flows through a typical multiple-cyclone vacuum cleaner. In this model:

- Air enters through the brush bar at the bottom.

- The air enters the first stage tangentially (perpendicular to the cylindrical dirt bin) and spins around the cyclone in the middle. The dirt particles swirl to the edge, fall downward, and collect at the bottom while the air is drawn up through holes in the cyclone itself.

- The somewhat cleaner air passes into the second, upper stage.

- Here, a similar process happens only with a number of smaller cyclones that remove much finer dirt particles.

- The relatively clean air passes through a HEPA filter. Since most of the dirt has already been removed, this filter doesn't really impede the flow of air through the machine.

- The air blows back into the room after passing through a second HEPA filter.

The motor unit (not shown on this drawing) and fan is located at the base of the machine in between the two back wheels.

Please note that this drawing is not an exact representation of what happens in a Dyson (or any other, similar machine): it's just designed to give you a very general idea of what's happening in a cyclonic cleaner. In a Dyson DC04, like the one photographed up above, the airflow is actually like this:

I've removed the cyclone and dustbin, moved it to the side, and turned it backwards so you can see clearly what's happening. The red line shows the airflow up to the point at which it enters the cyclone. The orange line shows the airflow after the air exits the cyclone. The air enters through the brush bar, passes up a pipe at the side of the machine to the top, where it enters the cyclone, spins around, passes through the upper HEPA filter, then leaves through a second pipe also near the top of the machine, before traveling back down another pipe to the fan and the lower HEPA filter and finally exiting just underneath the dirt bin.

If you'd like to know more, please refer to one of the patents in the reading list down below, where you'll find complete technical drawings and a detailed explanation of how everything works in an actual machine.

Water vacuums

When it comes to suction, conventional vacuum cleaners tend to... suck, for want of a better word. Bulging bags and clogged filters progressively reduce the airflow, making it impossible for them to pick up more dirt effectively. Without filters, however, they blow quite a lot of the finer dust (the harmful particles known as PM10s, smaller than 10 microns) back into your room; so, instead of "vacuum cleaning", they are simply "dust rearranging": sucking in dirt and blowing it back out so it settles somewhere else. That's a particular problem for people with asthma or dust allergies. Even the best cyclonic vacuums aren't perfect: cyclones don't remove all the dirt, hence the need for those extra HEPA filters, which are typically either so fine that they clog up repeatedly (reducing airflow and cleaning power) or so coarse that they allow dirt back into the room.

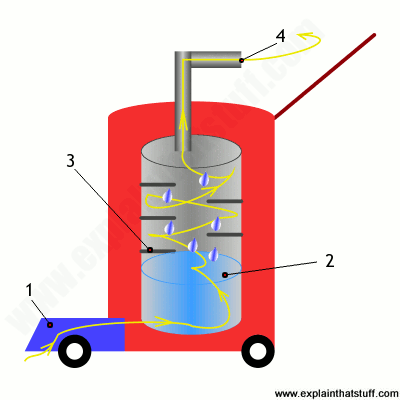

What's the solution? One option is to use a water vacuum, which uses a tank of water to trap the dirt instead of a bag or conventional dirt bin. The dusty incoming air fires into the water tank, where the dirt is held in solution. The moist air that leaves the tank is then spun around to remove the water (a bit like in a Dyson), producing clean air that flows back into the room.

Here's how a typical water vacuum works:

- Air is sucked in through the brush bar in the usual way.

- A powerful motor (not shown) pulls the air through a water tank, where most of the dirt is trapped.

- The moist air continues through the tank, spiraling past plastic plates, which help to separate out the water droplets from the air that carries them. The water drips back down into the tank.

- Clean, dry air exits through an outlet on top of the machine.

No comments:

Post a Comment