Why do keyboards have that strange QWERTY layout?

What happens when you press a key?

Here's the typewriter with the top cover removed. The keyboard is at the front. The paper moves from right to left on the carriage at the back. In between, is a complex arrangement of levers and springs. A typewriter like this is completely mechanical: powered entirely by your fingertips, it has no electrical or electronic parts. There's not a microchip in sight!

So how do you use it? The basic idea is simple: you press a key(1) and a lever attached to it (2) swings another lever called a type hammer (3) up toward the paper. The type hammer has the slug of metal type on the end of it. Just as the type is about to hit the page, a spool of inked cloth called a ribbon (4) lifts up and sandwiches itself between the type and the paper (5), so the type makes a printed impression as it hits the page. When you release the key, a spring makes the type hammer fall back down to its original position. At the same time, the carriage (6) (the roller mechanism holding the paper) moves one space to the left, so when you hit the next key it doesn't obliterate the mark you've just made. The carriage continues to advance as you type, until you get to the right edge of the paper. Then a bell sounds and you have to press the carriage return lever (7). This turns the paper up and moves the carriage back to the start of the next line.

Manual and electric typewriters

The first typewriters (and most portable typewriters, like the orange one shown in our first few pictures) were completely mechanical. A mechanical typewriter is a machine: everything is operated by finger power. The force of your fingers is what makes the ink appear on the page. That's why mechanical typewriters often produce rather erratic, uneven print quality—because it's hard to press keys with the same force all the time. When electric, semi-electric, and electronic typewriters became popular in the mid-20th century, they automated many of the things a typist previously had to do by hand.

Most electric typewriters do away with the system of levers and typehammers. In some models, the type is mounted on the surface of a rotating wheel called a golfball. Other models use a daisywheel, which looks like a small flower, with the type radiating out from the end like petals. The keys on the keyboard are effectively electrical switches that make the golfball or daisywheel rotate to the right position and then press the ribbon against the page. Because the type is hammered under electrical control, every letter hits the page with equal force—so a big advantage of electric typewriters is their much sharper, neater and more even print quality.

Photo: A daisywheel from an electric typewriter (small photo, inset right) is about as big as the palm of your hand. You can just about make out the raised letters, in reverse, in the close-up photo on the left. Each character is on a separate "petal" of the wheel. The upper- and lower-case versions of each letter are on separate petals too (unlike in a mechanical typewriter, where the upper- and lower-case letters are on the same type hammer).

There's another big difference from manual typewriters too. In a manual typewriter, the type hammer mechanism stays still while the paper (wrapped around a rubber roller on the carriage known as the platen) gradually moves to the left. In an electric typewriter, the paper and the carriage stay still while the golfball or daisywheel gradually move to the right. When you reach the end of the line, you press the carriage return key. The golfball or daisyweel whizzes back to the extreme left position and the paper turns up a line.

Making mistakes

Typing mistakes are one of the biggest problems with mechanical typewriters. If you hit the wrong key, it's already too late: you've made a permanent mark on the page. Similarly, if you change your mind about what you wanted to write, you can't easily erase what you've written. There are three ways around this difficulty. One is to use a special eraser to remove the type marks. It works just like a pencil eraser, but it rubs ink away instead of pencil. Another option is to use a correction fluid like Liquid Paper or Tippex (effectively a quick-drying white paint that covers up your mistakes). When electric typewriters appeared, they offered a much more convenient, third option: many of them had an auto-correction feature. This is a second ribbon, made of plastic and with white ink imprinted onto it. If you hit the autocorrect button on an advanced electric typewriter, the print mechanism moves back one space and automatically overtypes the last key you printed using the white ribbon. So if you typed H by mistake and hit autocorrect, the machine would go back one character, and type a white H on top of the black one—effectively removing it from the page. You could then type a different character on top.

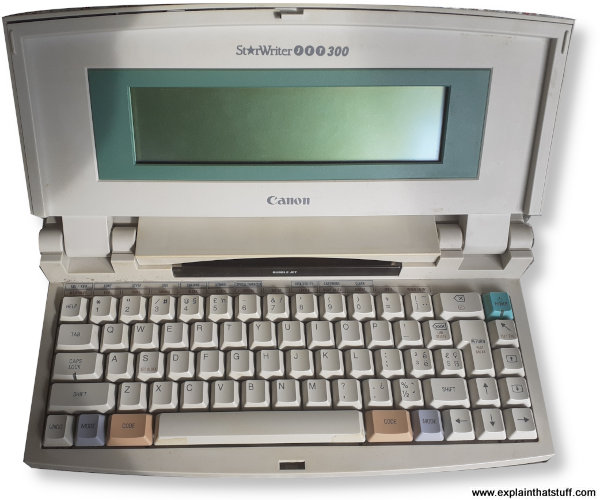

Electronic typewriters made typing mistakes a thing of the past. They're effectively a halfway-house between typewriters and computers: they look like typewriters, but they have completely electric keyboards and work like computers. They often have a little LCD display screen and the letters you type appear on there first. You can easily correct your mistakes on the display before printing anything out. Some electronic typewriters (like the popular Canon Starwriter series) have a large internal memory and a screen big enough to show about eight or ten lines of text. You can type several pages of text into the memory and play around with the formatting, just as you can on a computer. When you're finally satisfied with what you've written, you can print out the text or save it on a floppy disk.

Many more people have computers these days and hardly anyone uses mechanical typewriters. Indeed, now voice recognition is so advanced, some people don't even use keyboards! But typewriters were crucially important to the development of personal computers. The whole idea of a personal computer (a machine into which you type "input" and wait for written "output" to appear on the screen) is essentially based on a typewriter. You sit at a keyboard and peck away, one letter at a time. If you're using a word processor, what you see on the screen—letters slowly appearing and moving toward the right of the page as you type—is exactly what you would have seen on the paper in a typewriter.

No comments:

Post a Comment